Adam Steltzner

Adam Steltzner, in charge of the Entry, Decent, and Landing of NASA's Mars rover Curiosity, outlined the winding journey of his life in his Assembly Series lecture on March 26, 2015: “How Curiosity Changed My Life.” The lecture title was a deliberate play on words meant to emphasize the power of intellectual curiosity and how it can transform a life.

“When we’re exploring, we’re asking questions about ourselves. As individuals. As a society. As a people. We’re kind of searching for our potential. What’s the edge of us? What questions might we dare ask and hope to be able to answer?

It’s that curiosity that drives us to learn. And that learning is fundamental to us. Where will your curiosity next take you?”

For Adam Steltzner, the NASA engineer who was responsible for the Entry, Descent, and Landing (EDL) of the Mars Curiosity rover, this revelation marked the culmination of a long journey of self-discovery that began many years ago. Steltzner’s path to the NASA was atypical and it explains why he looks more like a member of a rock band than a NASA engineer. After high school, Steltzner became a rocker, and didn’t plan on going to college. But driving home from a gig one night, Steltzner noticed a change in the position of the stars in the night sky and was seized with an urgent need to find out why. From there, it was a long climb from community college to a Ph.D. in engineering mechanics at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, and eventually, to NASA and to the stars via Curiosity.

He outlined this winding journey in his Assembly Series lecture on March 26, 2015: “How Curiosity Changed My Life.” The lecture title was a deliberate play on words meant to emphasize the power of intellectual curiosity and how it can transform a life.

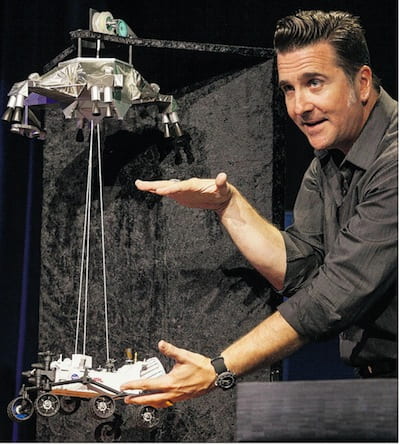

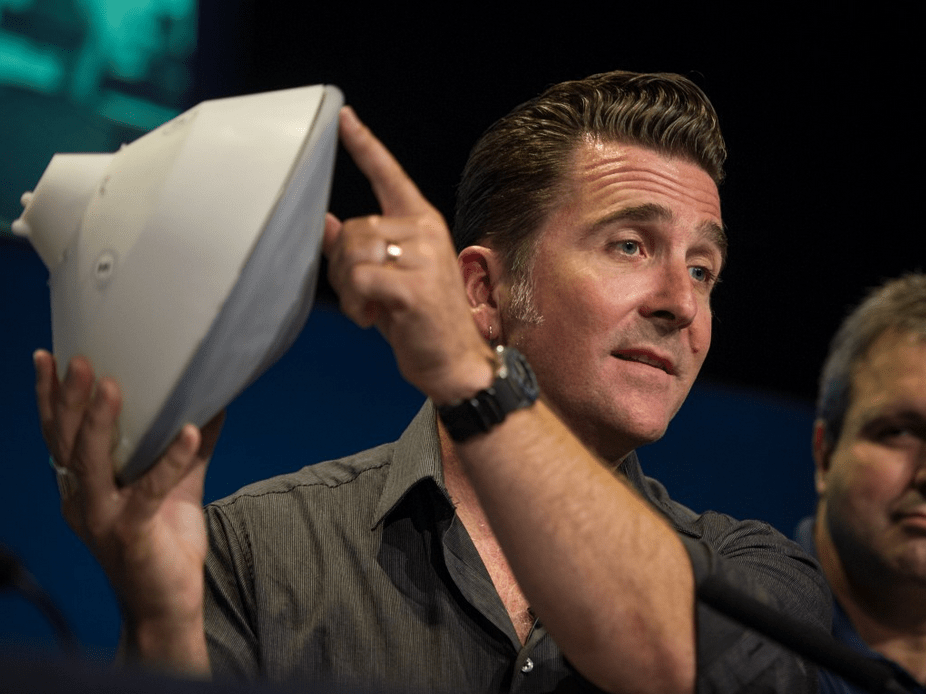

In one portion of the lecture, Steltzner explained the difficulties inherent in attempting to land a mini-cooper sized rover on Mars:

“The atmosphere, the atmospheric pressure, the makeup of the gravitational pull of the earth, all mean that we can’t test our design on earth…So you can’t test it. You have to analyze it. But the problem with analysis is that analysis only answers the questions you ask of it. You build a mathematical model with pen and paper, a 1s and 0s representation of a computer. And it will tell you about the features of the model. But it won’t tell you about what you forgot. So we did models…Several million models.

Steltzner wasn’t exaggerating the high stakes of his project. In fact, the EDL part of the Curiosity mission has been nicknamed the “seven minutes of terror” since the landing could only go one of two ways: success or failure.

The world celebrated with Steltzner’s team when Curiosity landed successfully on August 5, 2012; it continues to conduct significant research there.

Steltzner ended the lecture by urging us to think about our own curiosity:

“So she’s there. She’s doing great science. She is our curiosity. But I am left with an interesting question: Why do we do this? It’s a decade of my life. Millennia of human effort. Creating a robot to go to another planet. It doesn’t even seem like a particularly practical thing to do…we don’t explore because it’s practical.

It’s that curiosity that drives us to learn. And that learning is fundamental to us. Where will your curiosity next take you?”

Reaching a touchdown site 350,000,000 miles away seems unimaginable, but after Steltzner’s ruminative lecture, we are left with the idea that the power of curiosity is boundless and can inspire humanity to reach for the stars.